Discovering a 'Maker of Men'

One of the joys in checking out the availability of movies on YouTube and streaming sources is the stumbling on to something new to the viewer's experience. For this writer it was in discovering that AGGIE APPLEBY, MAKER OF MEN, a play by Joseph Otto Kesselring of ARSENIC AND OLD LACE fame, was made into a 1933 movie several years prior to the author's first draft of ARSENIC emerging from the typewriter. As Kesselring's other works that made it to the stage were nowhere nearly as successful as ARSENIC, this production of AGGIE APPLEBY, MAKER OF MEN, written by other hands, offers some insight into Kesselring's exploration of Great Depression social conditions in comedic terms.

One of the joys in checking out the availability of movies on YouTube and streaming sources is the stumbling on to something new to the viewer's experience. For this writer it was in discovering that AGGIE APPLEBY, MAKER OF MEN, a play by Joseph Otto Kesselring of ARSENIC AND OLD LACE fame, was made into a 1933 movie several years prior to the author's first draft of ARSENIC emerging from the typewriter. As Kesselring's other works that made it to the stage were nowhere nearly as successful as ARSENIC, this production of AGGIE APPLEBY, MAKER OF MEN, written by other hands, offers some insight into Kesselring's exploration of Great Depression social conditions in comedic terms.

Not that AGGIE APPLEBY, MAKER OF MEN, is a lost film or even one overlooked in its day. It was in fact routinely reviewed by newspaper critics and has gained something of a reputation as an example of the freer examination of contemporary mores before the Production Code stifled more adult-natured movies when heavier enforcement began in July 1934. A casual Google check unearths a wealth of discussion centering on AGGIE APPLEBY, MAKER OF MEN.

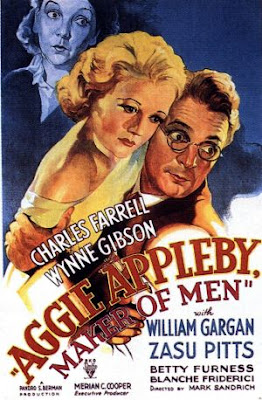

Directed by Mark Sandrich, and produced by Pandro S. Berman for RKO Radio Pictures (then still billing itself as Radio Pictures), AGGIE APPLEBY, MAKER OF MEN's titular heroine (Wynne Gibson) loses her inner New York City flat when her combative boyfriend Red Branahan (William Gargan), also a petty criminal, gets into one brawl too many and is sentenced to a prison term. Commiserating with her cleaning lady sister Sybby (Zasu Pitts), Aggie takes up residence in an apartment rented by Adoniram Schlump (Charles Farrell), a milquetoast from upstate looking to make his own way without the aid of his stifling Aune Katherine (Blanche Frederici). Tough-talking Aggie builds up "Schlumpy," as she calls him, gets him a job overseeing a gang of roughneck construction workers, and falls in love with her creation, even to the point of giving him her man's name of Red since the real possessor of the monicker is behind the wall for the time.

But the real Red, who redeems himself by helping quell a prison riot with his ready fists, is given an early release about the same time Aunt Katherine and the new "Red"'s fiancee Evangeline (Betty Furness) come to check in on him and bring him back to his nerdy former self. It all comes to a conclusion when Aggie, despite her feelings for "Schlumpy," does the right thing, sends him back to Evangeline (who rather likes the more assertive man he's become) and takes up again with the hopelessly dense Red.

AGGIE APPLEBY, MAKER OF MEN, as a play, was copyrighted by Kesselring on Dec. 3, 1932,* and apparently unable to find a backer for a stage production, he was successful in selling it to RKO. Merian C. Cooper, whose co-production with Ernest B. Schoedsack of KING KONG earlier in 1933 rescued RKO financially, had been rewarded with production chief duties following the departure of David O. Selznick to M-G-M. Cooper gave the green light to AGGIE APPLEBY, MAKER OF MEN to proceed. Chosen as director was Mark Sandrich, who had just left the shorts department at RKO following the success of the special subject SO THIS IS HARRIS. Sandrich's past experience came in handy with AGGIE APPLEBY, MAKER OF MEN as he skillfully guided the cast through the production, which was released Oct. 19, 1933.

AGGIE APPLEBY, MAKER OF MEN, as a play, was copyrighted by Kesselring on Dec. 3, 1932,* and apparently unable to find a backer for a stage production, he was successful in selling it to RKO. Merian C. Cooper, whose co-production with Ernest B. Schoedsack of KING KONG earlier in 1933 rescued RKO financially, had been rewarded with production chief duties following the departure of David O. Selznick to M-G-M. Cooper gave the green light to AGGIE APPLEBY, MAKER OF MEN to proceed. Chosen as director was Mark Sandrich, who had just left the shorts department at RKO following the success of the special subject SO THIS IS HARRIS. Sandrich's past experience came in handy with AGGIE APPLEBY, MAKER OF MEN as he skillfully guided the cast through the production, which was released Oct. 19, 1933.

Indeed, AGGIE APPLEBY, MAKER OF MEN, scripted by Humphrey Pearson and Edward Kaufman, bore similarities to the Cooper-produced feature RAFTER ROMANCE, directed by William A. Seiter that had premiered in September. Both explored the theme of a mismatched everyday couple forced by circumstances and income to share living quarters in the big city. While AGGIE APPLEBY, MAKER OF MEN's main characters were more broadly drawn than those portrayed by RAFTER ROMANCE's leads (Ginger Rogers and Norman Foster), both were very much of their time and unique in the strength exhibited in each production by Gibson and Rogers. The kind of brass displayed by Gibson, which extended to a brief yet no-nonsense sequence in underdress before co-star Farrell, disappeared with the institution of the code the following summer.

Reviews were mixed over AGGIE APPLEBY, MAKER OF MEN upon its release. Mordaunt Hall of The New York Times, however, recognized the energy and boisterous nature of the story, although in his view, because the film "was evidently written with an eye on the box office, the intriguing theme falls far short of what it might have been." But, he added, "in its rather crude fashion, this offering affords a good deal of amusement."**

Sandrich became director of several of RKO's music and dance extravaganzas featuring Rogers and Fred Astaire before moving on to Paramount, where he helmed a number of important features before his untimely death in 1945. Co-stars Gibson (1898-1987) and Farrell (1900-1990) are solidly convincing in their roles and had excellent support from Gargan and Pitts. Gibson had made her screen debut at the dawn of the sound era and continued through the '30s with roles of decreasing importance; her last cineamtic appearance was in 1943's MYSTERY BROADCAST. Farrell was already a romantic idol based on his work with Janet Gaynor in the silent classics SEVENTH HEAVEN (1927) and STREET ANGEL (1928). Encountering no difficulty in having his voice "register" with the microphone, Farrell moved effortlessly into talkies until the early '40s, when he left the screen to pursue lucrative land development at Palm Springs.

Pitts, of course, had already established herself as a comedienne of some standing for more than a decade when she took the role of Sybby in AGGIE APPLEBY, while Gargan, who'd entered films in 1932, found himself in great demand in parts less aggressive than that of Red. For Frederici, the movie was one of her last due to her passing just prior to Christmas 1933 at 55. Furness, 16 and an model when she signed with RKO in 1932, already had a few films to her credit when AGGIE APPLEBY, MAKER OF MEN was produced; like Farrell, her greater fame came with 1950s television and later, as a consumer affairs advocate.

For Kesselring, the prestige of seeing one of his works made into a movie was perhaps worth more than the amount RKO paid him for his play, making up for the disappointment in not seeing it on the Great White Way. Although some sources, possibly feeding off RKO publicity, indicated AGGIE APPLEBY, MAKER OF MEN had been produced for the stage to great success, no record exists of the play getting produced anytime before or immediately after the film version's release. By then, Kesselring had chosen to devote himself fully to writing after stints as a music teacher, actor, vaudeville performer and short story writer. The New York City native later credited his brief stint as an instructor at Bethel College, a Mennonite institution in Newton, Kan., during the early '20s as the inspiration for his one true success, the dark comedy ARSENIC AND OLD LACE.

Kesselring's official Broadway debut came with the Oct. 30, 1935, premiere of his comedy THERE'S WISDOM IN WOMEN, produced at the Cort Theatre by D.A. Doran with staging by Harry Wagstaff Gribble. The production was headlined by screen actor Walter Pidgeon on the verge of his lengthy association with M-G-M, with support provided by Ruth Weston, Glenn Anders and Betty Lawford. The show logged 46 performances before closing that December.

Another comedy, CROSS-TOWN, debuted March 17, 1937, at the 48th Street Theatre, produced by John Dietz and directed by William B. Friedlander. This production starred Joseph Downing, the original Baby Face Martin of the 1935 staging of Sidney Kingsley's DEAD END, with Vaughan Glaser and Mary McCormack in support. But it proved another disappointment for Kesselring, seeing its final curtain after five performances.

Development of ARSENIC AND OLD LACE, which Kesselring initially titled BODIES IN OUR CELLAR, has been well-documented by other sources and is generally accepted as owing much of its acclaim as a classic of American theatre to the influence of producers Howard Lindsay and Russel Crouse.

Both men generously gave the credit to Kesselring since it was his idea to begin with, but there is a strong belief that Lindsay and Crouse either performed a full-blown rewrite or at the least added "humorous embellishments" to the original draft, as theatrical historian Stanley Richards pointed out. "Though they consistently denied this, it was logical that the suspicion persisted, for Lindsay and Crouse had an almost unbeatable track record in the comedy department and were old hands at doctoring as well as creating," Richards added.***

ARSENIC AND OLD LACE premiered Jan. 10, 1941, at the Fulton Theatre under the direction of Bretaigne Windust. The cast was headlined by Boris Karloff as homicidal Jonathan Brewster, although the horror movie star always considered himself a supporting player to his character's lovable but dotty maiden aunts portrayed by Josephine Hull and Jean Adair. The show establised a record of 1,444 performances on Broadway, running continuously until June 1944, with a film version directed by Frank Capra for Warner Bros. appearing later in the year. The movie adaptation, starring Cary Grant as hero Mortimer Brewster along with Hull, Adair and John Alexander reprising their stage roles, had been shot in 1941 but was held up for release until the theatrical version finished its run.

An element in the play, either Kesselring's creation or that of the producers, is the depiction of Mortimer, initially essayed on stage by Allyn Joslyn, as possessing a number of the faults of his character's profession, a know-it-all theater critic. At mid- point in the second act as danger looms in the background from Jonathan, Mortimer cannot help but regale Jonathan's assistant Dr. Einstein with a pan of a thriller he had recently skewered in print, citing how dense the hero is for allowing himself to be caught in a house full of murderers. Some scholars have taken the digs at fatuous critics of Mortimer's stripe to be a venting of the author's and producers' hostilities toward reviewers. This is more understandable on Kesselring's part given that poor notices helped sink his previous vehicles, although Lindsay and Crouse may have taken some delight in deflating Mortimer's pomposity.

Kesselring presumably profited well from ARSENIC, which soon became a favorite of school, amateur and summer stock venues all over the country, remaining so as late as this summer. Although he continued writing for other markets, a full decade elapsed before his next play, FOUR TWELVES ARE 48, was staged early in 1951 and disappeared after two performances. MOTHER OF THAT WISDOM next appeared and slipped away in 1963, four years prior to Kesselring's death at 65.@

Overall, the author penned a dozen plays over the course of his career. But the production of AGGIE APPLEBY, MAKER OF MEN as a film and not as a stage vehicle, provided the author with a sense of accomplishment as well as some no doubt needed funds in those Depression days in which it was produced.

* Turner Classic Movies Overview of AGGIE APPLEBY, MAKER OF MEN, retrieved Aug. 19, 2017.

** Hall, "Wynne Gibson, Charles Farrell, William Gargan and Betty Furness in AGGIE APPLEBY, MAKER OF MEN," NYT, Oct. 20, 1933.

*** Richards, ed., BEST MYSTERY AND SUSPENSE PLAYS OF THE MODERN THEATRE, New York: Dodd, Mead & Co., 1971, p. 412.

@ Stephanie Chidester, "About the Playwright: Arsenic and Old Lace," Utah Shakespeare Festival, 2001, retrieved Aug. 19, 2017.

Comments

Post a Comment